Chugging Along

In addition to America’s seven Class I railroads, there are more than 550 short lines capable of carrying the same products, often handling the first and/or last leg of a freight move by rail. These short-line railroads ensure smooth transitions and are focused on improving switching and port facilities, with growing emphasis on the latest technologies. They’re also placing themselves at the forefront of environmental and safety developments.

It’s all part of the heavy investments short-line railroads are continually making, beginning with acquiring and restoring abandoned and nearly abandoned lines. Acquisitions are also continuing, though not always of rail lines.

“Since the economic recovery, traffic on short lines has taken off,” says Jo E. Strang, vice president of Regulatory Affairs at the American Short Line & Regional Railroading Association (ASLRRA) in Washington, D.C. “Forty percent of all rail moves have some sort of movement on a short line. What short-line railroads offer is better safety records, usually good relationships with their customers and better connections to other railroads. So you don’t have to transfer the goods. It’s a seamless type of transportation movement.”

Peoria, Illinois-based Pioneer Railcorp is currently rehabilitating the recently acquired Maumee & Western Railroad Corp.—now known as the Michigan Southern Railroad Co.—that had suffered from deferred maintenance under previous ownership.

“We purchased this line with the knowledge it is in dire need of rehabilitation,” CEO J. Michael Carr said when Pioneer was starting the process. “Our objective is to rehabilitate the line in order to provide consistent freight-rail service to current and potential shippers.” Track restorations also will provide additional line connections to Class I carriers, he explained.

With the addition of Maumee’s 51 miles of track in Indiana and Ohio, Pioneer now has 25 subsidiary rail operations in 14 states, with more than 600 miles of track serving more than 100 customers.

Darien, Conn.-based holding company Genesee & Wyoming Inc. (G&W), which now owns 113 short-line railroads, acquired the Arkansas Midland Railroad, the Prescott & Northwestern Railroad and the Warren & Saline River Railroad this January. The company also acquired the Rapid City, Pierre & Eastern Railroad last year and, in 2012, acquired Jacksonville, Florida-based RailAmerica Inc., the owner and operator of 45 short-line railroads in 28 states and three Canadian provinces.

“G&W companies serve 41 U.S. states and four Canadian provinces—significantly more than any Class I railroad—and interchanged 1.7 million carloads with Class I railroads in 2014,” says Michael E.

Williams, the company’s vice president of Corporate Communications. “As the first and last mile to customers, our railroads work closely with the Class I railroads to develop optimum service offerings. By combining the local knowledge and operating flexibility of our short lines with the operating efficiency and network reach of our Class I partners, our customers benefit from a seamless rail-service product.”

With the May 2014 startup of the Rapid City, Pierre & Eastern Railroad from an acquisition, Williams explains, agricultural products have become G&W’s largest commodity group. And, he adds, “the transformation of North American energy markets as a result of hydraulic fracturing is reflected in the amount of inputs and outputs transported by our railroads.”

Jacksonville, Florida-based Patriot Rail Co. LLC, which owns 13 short-line freight railroads with 500 miles of rail in 14 states, is among the short lines that have been acquiring more than just competitive railroads. It also acquired a railcar repair and cleaning service provider in Keysville, Virginia, in December 2013.

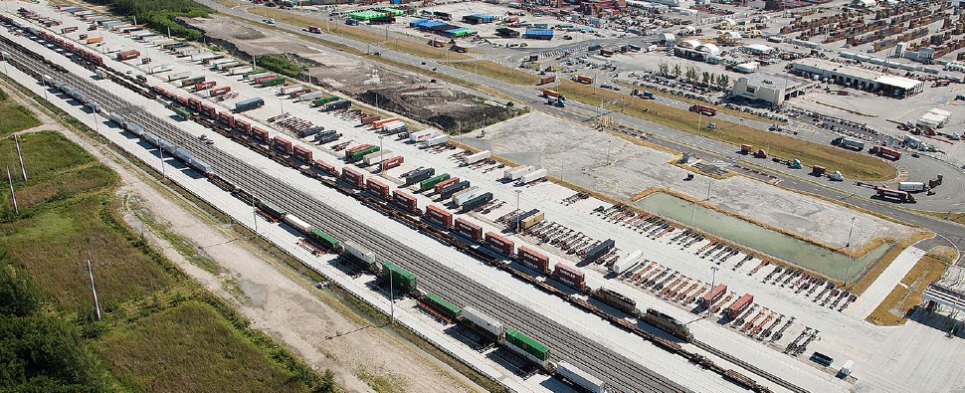

Florida East Coast Railway (FECR), also based in Jacksonville, has invested $35 million of a $53 million construction budget to “open up the centrally located Port of Everglades to both domestic and international shipping,” with the development of a new intermodal container transfer facility—the nation’s first portside rail yard to process both domestic and international cargoes, according to the railroad’s president and CEO, James R. Hertwig.

Built on 43 acres of land contributed by the port, the facility includes 21,000 feet of processing and storage track, separate domestic and international gate complexes, 11 automated gate system (AGS lanes) and the latest technologies that identify trucks, trailers and containers entering and leaving the terminal.

FECR’s rail line has five intermodal container transfer facilities or terminals, Hertwig notes. “Seventy-eight percent of our loads are intermodal. Intermodal reliability is crucial to the advancement of U.S. exports.”

The company, whose 351 miles of track runs from Miami to Jacksonville where it connects with two Class I railroads, contributed $9 million toward the cost of restoring rail to the Port of Miami. Completed in August of last year, the project replaced a 30-mile truck route, Hertwig says. “Rail is a lot more efficient than truck,” he says, noting rail’s importance given the trade increase expected now that PortMiami has dredged down to 50 feet of water to become one of only three East Coast ports capable of handling the mega ships soon to traverse the Panama Canal.

With all these developments, FECR is looking to improve service to existing customers and attract more companies to locate along rail lines. And like many other short lines, FECR has been acquiring locomotives that are more fuel-efficient and environmentally friendly, 24 of which were delivered in December 2014.

The entire 25-locomotive fleet of Wilmington, Calif.-based Pacific Harbor Line, Inc. (PHL) meets or exceeds the Environmental Protection Agency’s stringent Tier 4 emission standards, mostly as a result of retrofitting, according to company president Otis L. Cliatt II, whose firm serves the ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach.

PHL, a division of Anacostia Rail Holdings, started in 1998 as a dispatch-only outfit; it didn’t even have any locomotives.

“Our business continues to grow,” Cliatt says, “because with Class I railroads’ economies of scale it makes better sense for them to haul traffic than do switching. And here within the port, the majority of PHL’s switching is customized for each of the separate marine terminals. We have nine on-dock intermodal marine terminals that are serviced by rail within the port complex and each of them has its own customized switching that we do. That would be much more challenging for a Class I to do.”

With Class I railroads Union Pacific and Burlington Northern Santa Fe as PHL’s largest customers, “We’re the first mile and the last mile for global trade,” Cliatt says.

At municipal-owned Tacoma (Washington) Rail, which has more than 200 miles of track, “all the switching work that Class I railroads don’t like to do is done by us,” says Dale W. King, superintendent and COO, “and our line operates all of the Port of Tacoma-owned infrastructure.”

Logs and finished timber were major export products at one time, but that started to wane in the 1980s. King says Tacoma Rail then opened Port of Tacoma’s first on-dock intermodal facility.

“So as one business went away, another business began to grow,” King points out. “Over 50 percent of Washington State’s gross product is dependent on trade. We handle a fair amount of that business as it comes in by railcar and gets loaded into containers. Up through the Great Recession, about 80 percent of our business was international intermodal, providing the interface between the port and the national freight rail system.”

The additions and improvements to America’s short-line railroads has American Short Line & Regional Railroading Association’s Strang feeling optimistic. “They’re efficient, they’re safe and they’re growing their traffic all the time,” he says. “The future for short lines is very bright.”

Leave a Reply